Van Buren: A victory for web scrapers

This month, in Van Buren v. United States, the US Supreme Court ruled that accessing permissible areas of a computer system with prior authorization, even for an improper or prohibited purpose, is not a violation of the CFAA. This is a big win for the web scraping community, as clarity on the breadth of this law has been something many web scrapers have been waiting for. So let’s talk a bit about what exactly this means for web scrapers . . .

The CFAA, which stands for the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, is a United States law that many feared could be interpreted as making web scraping a criminal act. This law, which is often referred to as the federal “Anti-Hacking Statute”, was put into effect in the 80s at a time when the landscape of the internet was very different. One can be criminally liable under the CFAA for intentionally accessing a computer without authorization or exceeding authorized access. The scope of the CFAA is very broad, as it encompasses information from every computer connected to the internet, with computer being defined as most electronic processing devices. Violation of the CFAA could result in large fines and/or up-to 10 years of jail time, as well as being included as a private cause of action in a lawsuit. Cybercrime has changed dramatically since 1986 and courts struggled with how to properly apply the CFAA to today’s reality. Until last week, the application of the CFAA varied across jurisdictions of the United States. Given the possible jail time, it’s easy to see why the uncertainty of the scope of the CFAA was a concern for web scrapers. The United States Supreme Court laid the disagreement to rest this month in what can be seen as a victory for web scrapers.

Nathan Van Buren was a police officer in Georgia. As a part of his job, Van Buren had access to the police database with his own valid credentials. The police department had a policy of prohibiting use of the station database for personal reasons, which they described as an improper purpose. Van Buren was briefed on this policy but still used the police database to search for a license plate outside of the scope of his work in exchange for money. The US Government viewed this violation of the police station’s policy as a breach of the CFAA and charged him with a felony under the clause of the CFAA that makes it a punishable offense to intentionally access a computer without authorization or exceed authorized access to obtain information from a protected computer. Van Buren was found guilty and appealed to the Eleventh Circuit, who shared the Government’s view. Van Buren then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that he did not exceed his authorized access as he was entitled to obtain the information, which should not be a violation under the CFAA- a view that many other courts in the US agreed with.

Prior to the Van Buren ruling, there were two conflicting positions on how to interpret the CFAA. The first, which the Government and Eleventh Circuit took in this case, is that any misuse of access to a computer system for inappropriate reasons is a violation of the CFAA. The second position, which Van Buren argued, is that the CFAA is only violated if information is obtained is information that a user does not have access to. This second position would reduce the scope of the CFAA to hackers and other bad actors. If the first position were applied, violating your employer’s internal policy or a minor breach to a website’s terms of service could subject you to criminal charges and possible jail time. The Supreme Court agreed that this interpretation would “criminalize everything from embellishing an online-dating profile to using a pseudonym on Facebook” and “attach criminal penalties to a breathtaking amount of commonplace computer activity.”

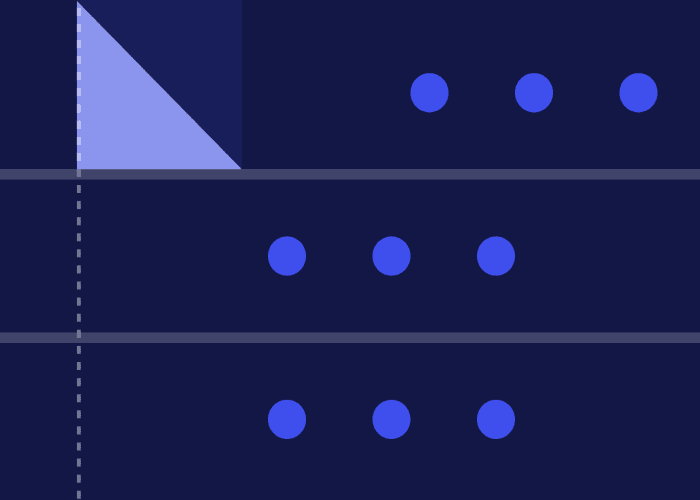

In applying this clarified reading of the CFAA, there are two questions to ask here:

- Do you have authorization to use the computer system?

- If no, then the gate is down and proceeding to use the computer system could be a violation of the CFAA.

- If yes, the gate is up and you can proceed to the next question.

- Do you have authorization to access certain information or files within that computer system?

- If yes, then the gate is up and there should not be a violation of the CFAA even if you are accessing that information for an improper purpose.

- If no, then the gate is down and proceeding to access the information could be a violation of the CFAA.

Van Buren was authorized to access the police database on his patrol-car computer and his credentials gave him access to the information. Even though his use of the police database was improper and outside the scope of his work, the Supreme Court ruled there was no violation of the CFAA as he had authorization to access that information. The circumstances do not matter: you either have access or you don’t. This is great news for web scrapers. If you have authorization to use a computer system or to access a website, for whatever reason, then you do not exceed that authorization under CFAA when you access the site to scrape the data even if your actions are potentially prohibited in some other way.

There is still an ongoing case to follow between LinkedIn and HiQ, which the Supreme Court sent back to the Ninth Circuit for a decision in light of the Van Buren ruling. It is important to note that the Supreme Court specifically put off the question of whether access is determined by technological or code-based limitations, or whether access could also be limited by contracts (such as terms of service) or policies. It is unlikely the Supreme Court will come back to this question in the near future, so the LinkedIn case could give us further insight on how this will be interpreted by courts moving forward. Van Buren is a great stride forward for web scraping and we hope to see the Ninth Circuit follow suit and continue on this path toward open access to web data for all.

Remember, I’m a lawyer but I’m not your lawyer, so it’s always best to get your legal advice from your lawyer. If you are concerned about how the Van Buren case directly affects your practices, check with your lawyer. There are still other considerations regarding the legality of web scraping.

For more on that, please take a look at our previous blog posts: